Two Songs Sung by Pete Seeger

The older I get the more I realise how formative certain primary school experiences were upon my adult wordview. A lot of the hymns I had to sing at my Church of English primary school were confusing or troubling to me. Perhaps triggering my childhood OCD most severely was the Quaker hymn ‘When I Needed a Neighbour’ . The imperative to serve others was not lost on me, but the rhetorical pleas of the third verse’s cold and naked man asking “Were you there?” caused tremendous guilt in this 6-year-old who did not know how to approach, let along help, a cold and naked person, and under what circumstances it would be appropriate for him to do so.

The “hymns” I enjoyed singing along to in assembly the most were not, in actual fact, hymns at all, but left-wing folk songs popularised by Pete Seeger. There was no way for me to know (not having been informed by any teacher) that the hammer of ‘If I Had a Hammer’ was the hammer of the Progressive Labour movement, though we might have been told that it was a Civil Rights songs. Truthfully I just liked the idea of someone enthusiastically hammering all over the world – more literally than metaphorically!

The two songs that got mixed in my head (and still do so that singing one can easily transform into singing the other) were ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone?’ – which Seeger wrote with inspiration from the Cossak folk song ‘Kolada-Duda’ to a traditional Irish folk melody – and ‘Little Boxes’, written and composed by Malvina Reynolds, later covered by Seeger.

‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone?’ could move me to tears as a little child and still has the ability to do so if it catches me when I am feeling fragile. The fact that even a little child can grasp its message and that it has been covered across the globe in many different languages speaks to the universality of the sense of e̶c̶o̶l̶o̶g̶i̶c̶a̶l̶ loss that it captures. Of course, it is actually an anti-war song. The flowers that are gone have been picked to put on war graves of the young men the girls are no longer able to marry. However, this meaning is only grasped by the song’s subsequent verses. In the first verse we hear:

Where have all the flowers gone?

Long time passing.

Where have all the flowers gone?

Long time ago.

Where have all the flowers gone?

The girls have picked them every one.

Oh, When will you ever learn?

Oh, When will you ever learn?

The most obvious interpretation when faced with that first verse is that the flowers are all gone because the girls have picked all of them – withholding from doing so is the lesson they need to learn. This is not as goofy a reading as it might first appear! The second verse asks where the young girls have gone and we discover that they have gone for husbands, every one. It is only with the third verse that we find out that the husbands themselves are gone because they have disappeared to war.

This escalating, repetitive structure in which the information provided by a subsequent verse illuminates the ones preceding it, is a lyrical structure Seeger was adept at using to reveal his social/ political message. An illustrative example is his brilliant and disquieting ‘What Did You Learn in School Today’, in which the first verse reads:

I learned that Washington never told a lie

I learned that soldiers seldom die

I learned that everybody's free

And that's what the teacher said to me

That's what I learned in school today

That's what I learned in school

So, we have the school functioning as what Althusser called an ideological state apparatus filling children’s heads with propaganda to encourage them to unquestioningly serve their country in war. The final verse of the song reads with grim predictability:

I learned that war is not so bad;

I learned about the great ones we have had;

We fought in Germany and in France

And someday I might get my chance

And that's what I learned in school today

The work of militaristic state indoctrination is complete and the child is ready to grow up to fight (and die) for his country.

However, we do not typically read songs, we hear them. On the page, the question ‘Where have all the flowers gone?’ presents as a mystery – the reader’s eye can quickly skip ahead to ascertain that they are reading the lyrics to an anti-war song and that these flowers are linked at the end of a chain of cause-and-effect to the deaths of soldiers, with their graves “covered with flowers every one”. In this reading, the flowers function metaphorically as representations of the dead men, like the poppies in Flanders Field or worn on the breast on Remembrance Sunday.

Yet, I suggest to you, that we do not listen to songs (especially ones we first encounter as children) in the same way as we read lyrics. Listening, we encounter free-floating images as we catch (or sometimes mishear) the words being sung, sometimes linking verses together, but often understanding them independently but in relation to a repeated chorus. Moreover, the parts we play over in our heads when a song becomes an ear worm may well be limited to a snatch of melody – a song’s opening few lines repeated ad infinitum. So, for me – rightly or wrongly – I largely forgot about the men in unform, with “Where have all the flowers gone? Long time passing” repeating in my head in a melancholy, unanswerable cycle.

That rhetorical question, whether intended by Seeger or not, captures the uncomprehending sense of loss that many of us experience when faced with the biodiversity crisis. For me, living so far relatively undisturbed by extreme weather events here in Suffolk, England, biodiversity loss is far more immediate and tangible than the hyperobject that is climate change. I can remember rhododendrons in the village where my parents live used to swarm with butterflies in the summer. I can remember how as soon as you ushered one fly out of the window it was seemingly replaced by another one, and when you went for walks you’d have horse-flies nipping at your ankles. You’d see stag beetles fighting on the tarmac and billywitches would fly down the chimney. Fields would be peppered with daisies and dandelions. So often now the countryside here is eerily silent, denuded of insects and birds. And it does feel like a long time passing. I was often anxious and unhappy as a child, but it still feels as though nature gave us a cornucopia which we upended into the trash with a shrug. In exchange for what…?

Well my childhood brain had an answer for that “Where have all the flowers gone? Little boxes on the hillside. Little boxes made of tickytacky.”

‘If I Had a Hammer’, ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone’ and ‘Little Boxes’ must have all been on the same side of the cassette of "children’s songs" that was played in my village primary school’s assemblies. ‘Little Boxes’ wasn’t written by Pete Seeger but by his friend Malvina Reynolds who wrote the song to critique the rise of suburban housing developments in San Mateo County, California [EDIT: Thank you to reader Simon Randall for the correction]. The little boxes are little houses made of cheap construction material in which the aspirational, conformist middle-classes live. Like ‘Flowers’ and ‘School’ the structure of the song is potentially cyclical, with the middle-class professionals – doctors, lawyers and business executives – who live in the little boxes, sending their children off to school, from where they will grow up, get comfortable middle-class jobs, and then move into similar suburban tract houses.

However, I think it is more interesting to read ‘Little Boxes’ and ‘Flowers’ dialectically. Indeed, Columbia Records released both tracks as the A and B sides of a 7" vinyl. Nature and suburbia have often existed in opposition to one another. To quote Drs. Swierk and Tennessen, “Globally, the growth rate of suburbanization is greater than the human population growth rate, and suburban cover now exceeds 25% of land in most developed countries. Suburban sprawl, essentially landscape conversion, is a major issue effecting biodiversity loss”.

[Okay, so I’m not consulting rigorously peer-reviewed research for this blog… Surburbia is going to continue to spread and remains aspirational for millions across the globe, so I think there is value in projects that seek to rewild suburbia.]

I am not so radically non-anthropocentric that I am about to argue that the loss of a flower is equivalent to the loss of a human life (though, tellingly, when my mother was required to design a super villain as part of a game her idea of the most terrible villain was a character named ‘Flower Destroyer’!) but I think the flowers in ‘Flowers’ hold a metonymic, not just a metaphoric, relationship to the dead soldiers on a deep intuitive level.

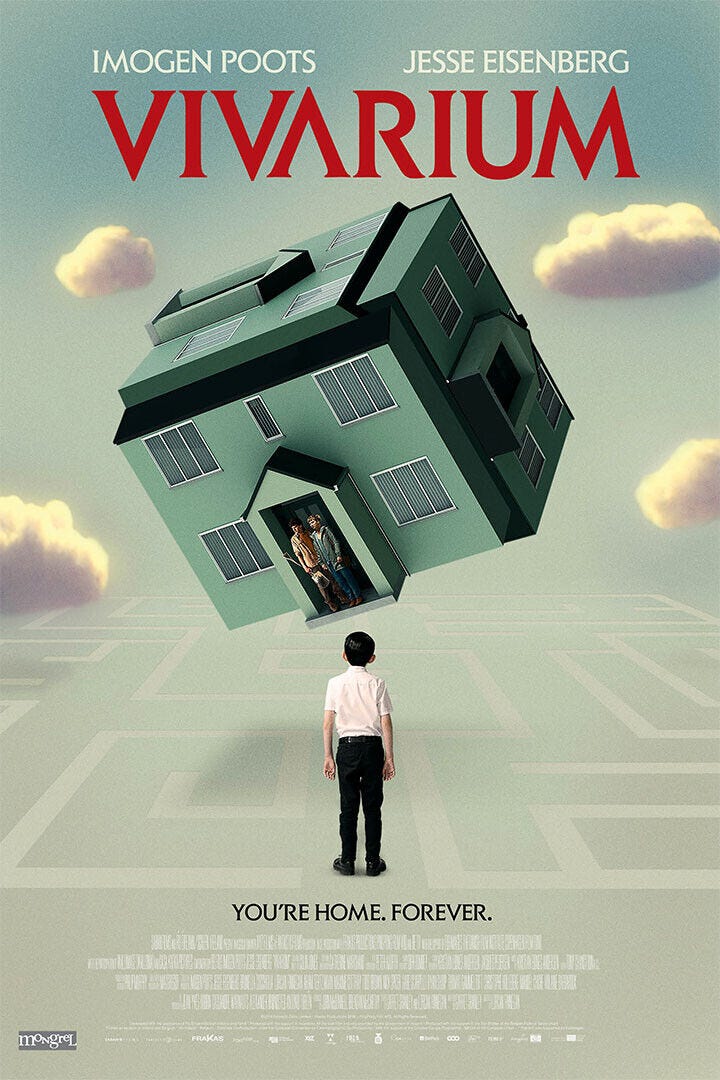

The makers of the 2019 film Vivarium grasp that the horror of suburbia lies not just in what is hidden behind the white picket fence, but adheres within the white picket fence itself. I think the film, while flawed, is worth watching, so I will avoid any major spoilers here, only to note that one of the parts of the film that I found most disturbing came not from body horror or anything explicit, but the revelation that the lawn of the surburban house belonging to the couple was actually a kind of astroturf.

There are many conventional, comfortable parts of our civilisation here in the Global North (and perhaps the UK in particular since I think parts of our culture are more kitschily comfortable than much of American culture) that are not only life-denying but ecocidal. Lawns, for instance, are one of the most genteel ways in which our civilisation wreaks havoc upon local ecosystems. While foreign wars ouside our borders displace death and suffering for those of us privileged enough to live in the counties that just grow rich off weapons rather than generally having to die at the ends of them, the poisons are home grown.

I’m sure I drunk my fair share of the proverbial Kool-Aid as a child, but I’m glad that I had the plain-spoken socialism of Pete Seeger to point out some of my society’s absurdities to me at a very young age. Another benignly left-wing influence was the work of Oliver Postgate. The Clangers live inside an asteroid in a society that is much more of an anarcho-syndicalist utopia than it is consumer-capitalist or even democratic. Sensibly, in the episode ‘Goods’, when faced with a barrage of tickytacky they quickly realise that they were much happier without… though usefully they also have the Froglets’ magic hat to disappear it all.

What media did you encounter/ were exposed to as a child that you suspect had a profound influence upon your long-term political beliefs? Please comment below!

Who can forget standing first thing each morning, hand over heart, in reverence to the flag, chanting the most violent national anthem in the world? "The bomb bursting in air!" Whoa. What a way to start the day!