This is a serious blog post, despite eventually being about a comedy programme. Please bear with me.

I have felt morally compromised in every job I’ve worked. Working in insurance was the worst. I was on the phones dealing with in-coming home insurance sales. The large insurance company was in charge of all sorts of brands. I was selling home insurance for a brand favoured by the upper-middle class. Straight up, I didn’t lose sleep over being unable to sell insurance to the person with a four-storey mansion living on a flood plain; though – with my ‘just doing my job’ excuse – they did compare me to a Nazi guard at Auschwitz, telling me my morals were “dead and spinning in their grave”.

Honestly, I tried to hold onto my moral integrity. Once, checking a customer’s insurance record on the computer, I noticed that due to a series of compounded errors made by several colleagues, he was paying several hundred pounds more for his insurance than he should have done. Whoops! I reported this to my supervisor. They didn’t understand why I was fussed.

“So, he’s not complained or anything?” they quizzed me, bemused.

“No”, I explained, “He doesn’t realised we’ve overcharged him.”

“So, what’s the issue?”

It took me seven attempts – I recorded the number – to convince my superiors that this customer should get his money refunded. After half-a-year of working there, I was told that to stay on I would have to sell travel insurance in which customers are penalised for getting cancer. I’d already listened into conversations in the office between supervisors about customers who had forgotten to renew their insurance because of dealing with the death of a close family member… and whether these customers should lose the discount they’d accrued by not making claims. How dispassionate was the company willing to make itself look? I chose not to renew my contract.

Sainsbury’s was a little better. I haven’t eaten pork since I was 13. So, I told myself I was respecting people’s individuals consumer choice when I sold them vacuum sealed packets of bacon and sausages. But I’ve seen how pigs dig their heels in when they’re being led to the slaughter house; how they scream. Many people in this country would have seen me as a monster if I’ve chosen to sell sliced up parts of the muscle tissue, fat and skin of dogs in exchange for minimum wage, though pigs are hardly less intelligent than dogs and just as social. So it goes.

As a ghost tour guide I was duping the credulous. As a library assistant I fined the disorganised and hapless. Working at a former polytechnic I was told by recruitment that I had to accept prospective students onto courses that I knew they’d be unable to pass. These students would scrape through their first – sometimes even their second – year… and then drop out when they realised they were unable to write a dissertation. £25,000 and change for some late mornings, conversations in a room and access to a library. When Covid hit and lockdowns were enforced, they got even less than that.

So, being a teacher at a state secondary school has been comparatively rewarding. However, it is also the job in which I am required to compromise my morality the most. Prevent training classes left-wing environmentalists on the same level as right-wing terrorist groups like the KKK. We are expected to teach British values even while the government demonises immigrants, the children of whom are often the best behaved, most respectful and most intelligent in my classes.

My course curriculum for The Merchant of Venice was put together during the alleged anti-Semitism crisis within the Labour Party. The content within the curriculum sensibly and necessarily engages with the anti-Semitism of the play, but also draws from Israeli resources and newspaper articles written during a period in which Jeremy Corbyn, then leader of the Labour Party, was “was thoroughly delegitimised as a political actor” (Cammaerts et al., 2016).

I taught this module during the first months of Israel’s invasion and bombing of Gaza. I had several Muslim students deeply upset and angry about what was (and is) being done to Palestinians; who wanted me to confirm that what they were (and are) seeing was (and is) a genocide.

So, I hedged my bets. Gave mush-mouthed measly, weasly answers. I said that I didn’t agree with bombing civilians and that it had not worked during the Vietnam War. When I gave the definition of anti-Semitism I did not go by the IHRA working definition but stated that it means discrimination and abuse against Jewish people, not criticism of Israel or the Israeli government.

I’m sure it’s not just me who finds this rhetorical hedging – condemning but not condemning too harshly – has left them morally withered and diminished. Like they’re a hollow person pupeeteered with broken sticks. Earlier I watched a video of a Palestinian girl tell me and everyone else in the Arab and Western world:

“What blood runs in your veins? From what clay are you made? If your own child faced this, would you stay silent? I have one word to say: I will not forgive you, neither in this world not hereafter. And I will ask my Lord not to forgive you either.”

Can I answer her? Can you? Aaron Bushnell did but children keep being murdered. We donate; maybe go to a protest or two. But mostly we keep on living within the system that helps ensure these deaths, keep on compromising ourselves within our jobs.

It is that grim moral calculus which the show Review (2014–2017) makes comedy out of. If my moving from the horrors inflicted upon Palestinian children to discussing a comedy show makes you sick and uncomfortable… that’s how the show made me feel. By the end of its three season run I wasn’t even laughing, but was watching it transfixed with a queasy horror of recognition I hadn’t experienced before. The pathology of the show’s main character is very much a pathology that I have.

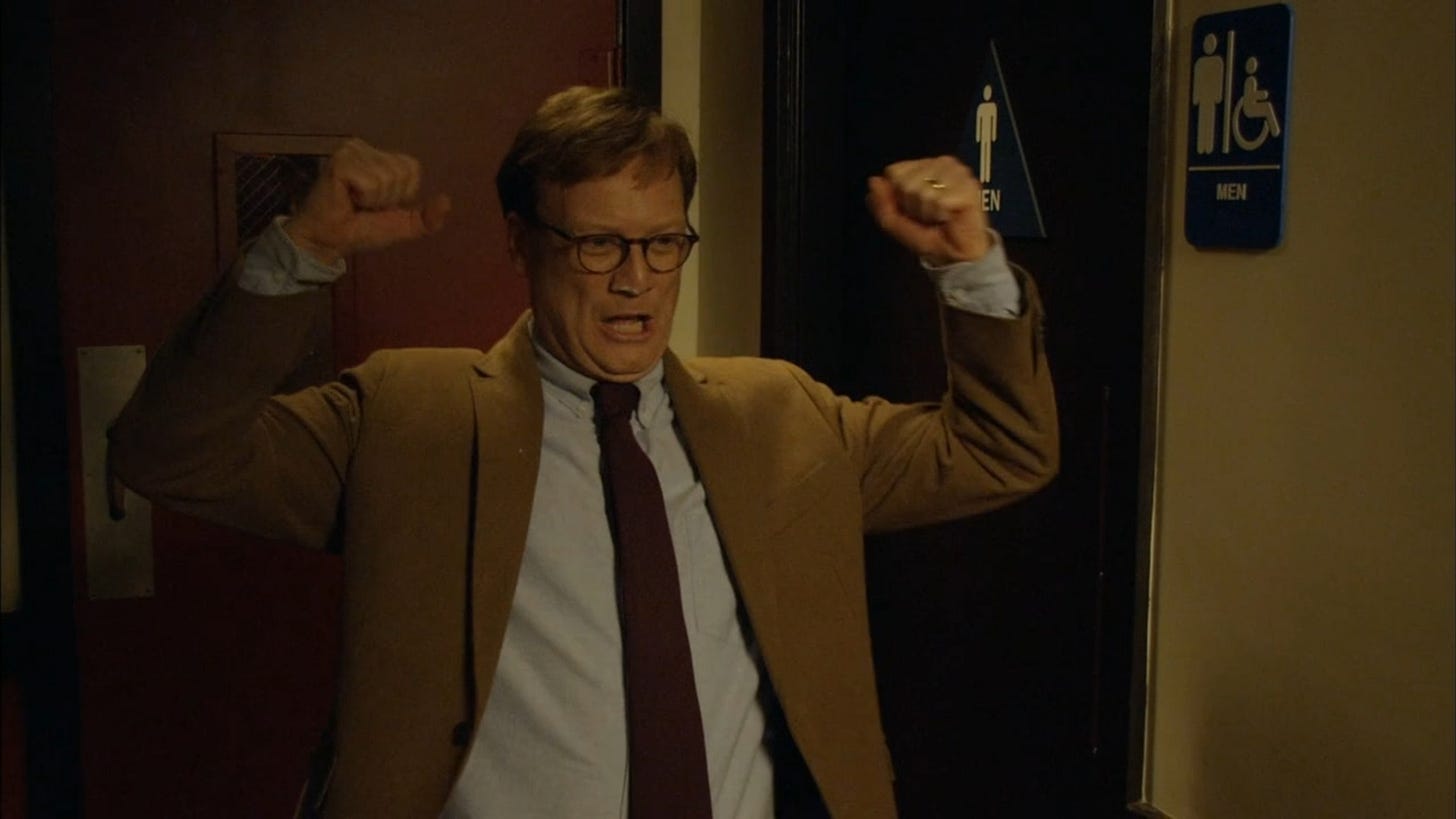

Review’s premise is that a former film reviewer, Forrest MacNeil (played by Andy Daly), presents a new show in which he reviews life experiences, grading them on a scale of half-a-star to five stars. Review is the in-universe review show that you, the viewer, are watching (alongside the fictional viewers who exist within the show’s universe!)

At first Forrest comes across as a pretty mild-mannered, oddly chipper man, notably enthusiastic about his new job and committed to the show’s tenuous premise. Forrest seems to regard his job as a genuine social good, allowing viewers to gain insight into life experiences they likely won’t have had and, as such, helping them to know whether to avoid or indulge in these experiences. From the start, Forrest’s idealistic conception of his job is contrasted against the combination of bromidic (‘eating 15 pancakes’) and mean-spirited, trolling experiences (‘being buried alive’) that members of the public request Forrest reviews. What is more, it quickly becomes apparent that Forrest’s unscrupulous producer, Grant Grunderschmidt (James Urbaniak), is filtering the submission to ensure that only the more entertaining and salacious ones get through.

While Forrest’s orientation towards his work is idealistic and Grant’s is cynical, other characters who work on the show represent other approaches to employment. Josh (Michael Croner), an unpaid intern, recognises he’s being exploited, but is too feckless and unmotivated to address the situation. Lucille (Tara Karsian) – Forrest’s executive assistant – is sarcastic and disrespectful, but remains loyal to Forrest and the show. Importantly, no matter what their individual stance towards ‘Review’ (the show within the show) is, they do their jobs and it keeps getting made, a show with no value.

Because, of course, one of the jokes of Review is that it is utterly spurious to attempt to review real-life experiences and then extrapolate some kind of objective judgement from a unrepeatable subjective experience. Moreover, Forrest is never organically having these experiences, but is doing so at the whim of the public and the behest of his producer. In early episodes in which he reviews stealing, being racist and making a sex tape, one of the jokes is that by neglecting the motivating factors behind stealing, being racist or making a sex tape (such as poverty, prejudice or some other social factor) Forrest is only ever simulating these experiences, while still leaving others at risk to the harms they might cause.

By the end of the first episode Forrest has already done various things that he never would have done had they not been required by his job. The implication here could be similar to those of the infamous Milgram (1961) or Zimbardo (1971) experiements i.e. by being placed within an official role and then given orders by someone in an apparent position of authority (Grant, the show’s producer) Forrest conforms to expectations and acts in harmful ways he wouldn’t have done when left to his own devices. Certainly, in the third episode, in which he is asked to review divorcing his wife, Forrest repeatedly and tearfully stresses that his wife is his best friend and that he is only divorcing her because it is his duty to the show, his job.

However, the darker implication throughout the show is that Forrest’s job has given him license to do stupid, self-destructive, masochistic things. In Lyotard’s “evil book” Libidinal Economy (1974) the Marxist philosopher posited that the worker masochistically enjoys his/her subjegation.

In the third episode, Forrest’s review of divorcing his wife is bookended by two reviews of eating pancakes. In the first review of eating fifteen pancakes, Forrest begins by wolfing down the pancakes, but grows lethargic and disgusted, force feeding himself sloppy pancake mush he mixes with water, which he chokes down, vomiting at the end of the review.

However, in the succeeding review of eating thirty pancakes, following the divorce of his wife, something changes in Forrest. He narrates:

“From somewhere deep and previous unknown there sprang a reserve of fortitude and courage… or was it resignation, or fatalism, or nihilism? Or perhaps I simply understood, from the darkest corner of my soul, that these pancakes couldn’t kill me because I was already dead.”

Okay, so this is bathos - elevated, tragic prose about eating pancakes.

But, I’ve seen the eyes of people who have worked in an insurance call centre for decades.

I’ve heard how astonishingly cynical older teachers can be when the staff room door is closed.

Sacrificing your morals for your work is a kind of death of the soul.

I don’t want to spoil too much more of Review since I think it’s really worth watching. However, by the end of it, when Forrest is asked to choose between his family and his job, you already know which one he’s going to pick.

Now, working for an insurance company is not the same as working for BAE Systems is not the same as being an IDF soldier. It’s also much hard to allocate percentages of blame when it comes to wrongs committed in our working lives than our personal lives. But the fact that we live in a system that requires so many of us to be compromised, to try to make these ghastly calculations in our heads, shows how broken and sick this system truly is. Review allows us to laugh at this fact, but it left me with a hollow feeling in my chest by its end.