Reflections on Walpole's 'The Castle of Otranto'

And its influence upon the horror genre

serendipity

noun formal

UK /ser.ənˈdɪp.ə.ti/

the fact of finding interesting or valuable things by chance

"One can go round making pleasant discoveries, which is surely the correct description of serendipity."

From the Hansard Archive

(Cambridge Dictionary Online, Accessed 09 July 2022)

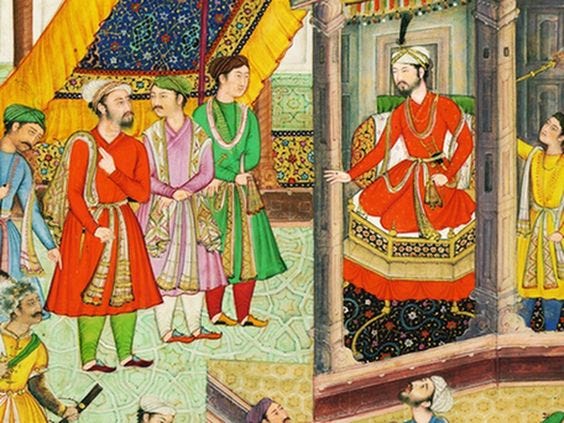

Horace Walpole, the 4th Earl of Orford, son of the first British Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole – dandyish, possibly asexual, and incredible prolific writer of letters – was the man who first coined the word 'serendipity', claiming to have derived it from a silly Persian-Italian fairy tale he had read, The Three Princes of Serendip. According to Walpole, in this fairytale, three princes identify the characteristics of a lost camel by, to quote Walpole, a combination of "accidents and sagacity".

Nowadays when we hear the word serendipity, we think of it as being interchangeable with 'good luck', but if we look at the events of The Three Princes of Serendip, we find that the princes are not so much lucky, as Sherlock Holmes-like in their ability to infer the lost camel's characteristics from seemingly random clues in their environment.

So, the princes, walking down a road, notice that the grass is less green on one side of the road that the other. They infer that on one side the grass is more fresh because it has been eaten. As such, the camel must have only been able to see the grass on one side of the road, presumably being blind on its other side. Tracks led to this grass. These tracks showed the prints of only three feet, alongside drag marks, showing that the camel must be lame in one foot. Even more remarkably, they infer from the fact that ants are in the grass on one side of the road and flies in the grass on the other, that the camel must have carried butter on one side of its back, honey on the other... The ants were attracted by the butter, while the flies were caught in the honey.

I describe the events of The Three Princes of Serendip to capture what I think attracted Horace Walpole so much to the story that made enough of an impact on him that he invented a whole new word inspired by it. I suspect that Walpole enjoyed the story's mixture of the ridiculous and the sublime, and the fact that the princes were able to take what might just seem quirky, random or weird to the layperson – there are a bunch of ants on this side of the road and a load of flies upon the other – and read them as omens or portents that reveal a deeper truth, the identity of the mysterious missing camel.

As I said, Walpole was the son of Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole. As expected of him, he went into politics himself. However, as a Member of Parliament he was, I think it's fair to say, pretty idle. He held the seat of the rotten borough of Callington in Corwall for thirteen years, yet in all that time he never once visited. He was not the kind of MP to have an open surgery where his constituents could go and visit him in the week to ask questions or voice their concerns. After some years in his early 20s spent travelling in France and Italy, he spent much of his time living and working from his home, Strawberry Hill, where he penned many hundreds of letters and reflections on art history and politics, which have proved an invaluable primary resource for later historians of the Georgian period.

When you hear the name Strawberry Hill, what do you picture? Perhaps a little tumbledown cottage in a bucolic English village, chickens in the front yard and an orchard in the back as the tune from the Beatles' 'Strawberry Fields' plays in your mind. This is not what Strawberry Hill looks like. Strawberry Hill is, in fact, a castle, albeit a very small one designed by Horace Walpole in the gothic style. It now sits at the edge of St Mary's University in Twickenham, London. And while Twickenham isn't central London – it's a leafy suburb on the River Thomas – Strawberry Hill still sticks out like a very white, ornated decorated thumb, pointing towards the Heavens with its tens of tiny spires. Like the story of The Three Princes of Serendip, it hard not to find Strawberry Hill House faintly ridiculous – charming, yes definitively – but a bit of a stretch... both of imagination and good taste.

Yet it was here, one dark night, that Horace Walpole had a nightmare that inspired him to write what would become widely regarded as the first gothic novel – The Castle of Otranto, published in 1764. At night you can imagine how the wine-red walls might appear clotted and bloody, the Rococo ceilings like intricate stalactites, moonlight casting Dario Argento shadows through the stained glass windows. In his dream Walpole saw a ghost stalking the corridors of his house, and the giant hand of a knight, clad in armor. Weird disconnected fragments. Inspired by this dream and his love of both Medieval art and Shakespeare’s history plays, Walpole began to write a story the likes of which the world had never seen.

In Shakespeare, phantoms and ghosts linger like oracles at the edges of the action. Hamlet’s father appears to him as a ghost, setting his tormented son’s hairs on end and speaking of “sulph'rous and tormenting flames”. The witches in Macbeth are like a Greek chorus, presiding over the action from the distance of the blasted heath, speaking in rhyme about dire portents conjured from their potions of eye of newt and toe of frog. Walpole takes the weird, grotesque imagery from the marginalia of Medieval illuminated manuscripts – and puts them front and center in his story – especially the startling juxtapositions in scale.

Take a minute to look up strange images from Medieval art. You might see knights fighting human-sized snails, castles built upon the backs of elephants, giant illustrated letters crawling with vines and flowers. In the opening section of The Castle of Otranto, the teenage prince Conrad is crushed to death under a giant helmet that falls from the sky. In the only major film adaptation of the book, Czech Surrealist Jan Švankmajer depicts this juxtaposition in scale through using a cut-up, collagist style of animation. Little figures, like those from a toy cardboard puppet theatre, are set against ginormous armored body parts. This style captures the stilted, artificiality of the novel’s prose, which always feels like one curious event after another, rather than a cohesive narrative. In this way, the experience of reading the novel is not unlike the experience of watching a narratively incoherent horror film late at night, such as Carnival of Souls, Susperia or The House by The Cemetery, albeit far less shocking or violent by modern standards. However, the dreamlike atmosphere has been retained, characters moving through corridors and underground passageways where they encounter inexplicable phantoms, such as a skeleton in a hermit’s cloak, and a giant spectral form, presumably the being who the helmet first belonged to.

Another aspect of the book that Švankmajer successfully translates is the fact that Walpole originally published it as a hoax. The novel’s original edition was published with the full title of The Castle of Otranto, A Story. Translated by William Marshal, Gent. From the Original Italian of Onuphrio Muralto, Canon of the Church of St. Nicholas at Otranto. Švankmajer maintains this premise by framing his 1977 film as a documentary, in which a reporter interviews a Czech doctor who claims to have located the original castle upon which Walpole based the castle of his story.

This framing narrative recedes into the background into a truncated version of The Castle of Otranto, in which the maniacal Lord Manfred, in the wake of his son’s death, seeks to wed his bereaved daughter-in-law, Isabella, who he hunts throughout the grounds of the castle. Rejected by Isabelle, Manfred eventually tried to murder her but, by mistake, stabs to death his own daughter, Matilda. With the death of his bloodline, the castle walls are shattered, much like the walls of the House of Usher in Edgar Allan Poe’s later story. In Švankmajer film, we hilariously cut back to the frame narrative, with the reporter casting his doubt upon the doctor’s story, until the walls of the castle behind them start to crumble. Finally, we see the doctor himself with him arm through the turret of the model of the castle, smashing it apart – whether to fulfill the book’s prophecy or in anger at the reporter’s lack of belief, it is hard to tell.

Clearly the castle itself is central to Švankmajer’s retelling of the story and it is perhaps the motif of the haunted house, with creaking corridors and secret passageways, that is the greatest gift the Castle of Otranto has given to gothic horror.

In an article for The Guardian, Jane Bradley reflects that “Set in a crumbling castle with all the now-classic gothic trappings (secret passageways, bleeding statues, unexplained noises and talking portraits), it [The Castle of Otranto] introduced the haunted house as a symbol of cultural decay or change.”

Likewise, Professor Nick Groom writing for the Oxford University Press, notes that “The action of Otranto takes place predominantly in the dark in a suffocatingly claustrophobic castle and in secret underground passages. Inexplicable events plague the plot, and the dead — embodying the inescapable crimes of the past — haunt the characters like avenging revenants. Otranto is a novel of passion and terror, of human identity at the edge of sanity. In that sense, Horace Walpole did indeed set down the template of the Gothic. The Gothic may have mutated since 1764, it may now go under many different guises, but it is still with us today.”

Perhaps it is serendipity that the novel is still with us in countless forms. It is an awkward piece of work, oddly placed between Medieval pastiche and an original tale of intrigue and terror. It is clearly the work of a man who read and wrote a great deal, but was limited in human experiences. Also, the films that resemble it the closest as not necessarily the greatest of the genre – the stumbling spooky incoherence of William Castle movies or the often rushed endings of Hammer Studios ‘60s output – feel more like The Castle of Otranto than the carefully managed plotting of, say, Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now or William Friedkin’s The Exorcist. However, with its threat of a monstrous patriarch, endless corridors, inexplicable apparitions, siblings and, of course, a haunted house, The Castle of Otranto is – in motifs if not in technical accomplishment or themes – a distant ancestor of The Shining. And, of course, in its opening claims of authenticity, it anticipates Tobe Hopper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre by some two hundred years. Without this work, the Gothic genre might not exist, and neither might two of the most popular and influential horror films of the 20th century.

Thank you for reading and please check out and read the references and, of course, the original novel itself.

Jane Bradley (2013) ‘Halloween spirits: literature's haunted houses’, The Guardian, 31 October. Accessed 16 July 2022 <https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2013/oct/31/halloween-literature-haunted-houses-horace-walpole>

Nic Broom (2014) ‘“There is no escape.” Horace Walpole and the terrifying rise of the Gothic’, Oxford University Press Blog, 03 October. Accessed 16 July 2022 <https://blogs.exeter.ac.uk/humanities/tag/the-castle-of-otranto/>

Horace Walpole, Mary Shelley and William Beckford (2006) Three Gothic Novels. London: Penguin Classics.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horace_Walpole

https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Castle-of-Otranto

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Three_Princes_of_Serendip