Reflections on the Work of Edgar Allan Poe

Some adaptations and the relationship between humour and horror in his works

How would it be if your worst enemy wrote your biography after your death? Would they provide a balanced portrait of your flaws and graces? Or would they characterise you at your lowest? Focus in upon the times you drunk too much, treated others badly, or failed to live up to your own standards? Would they invent some particularly nasty, salacious details with which to damn you with? What if that image of you was the one to dominate the popular imagination for nearly two hundred years after your death?

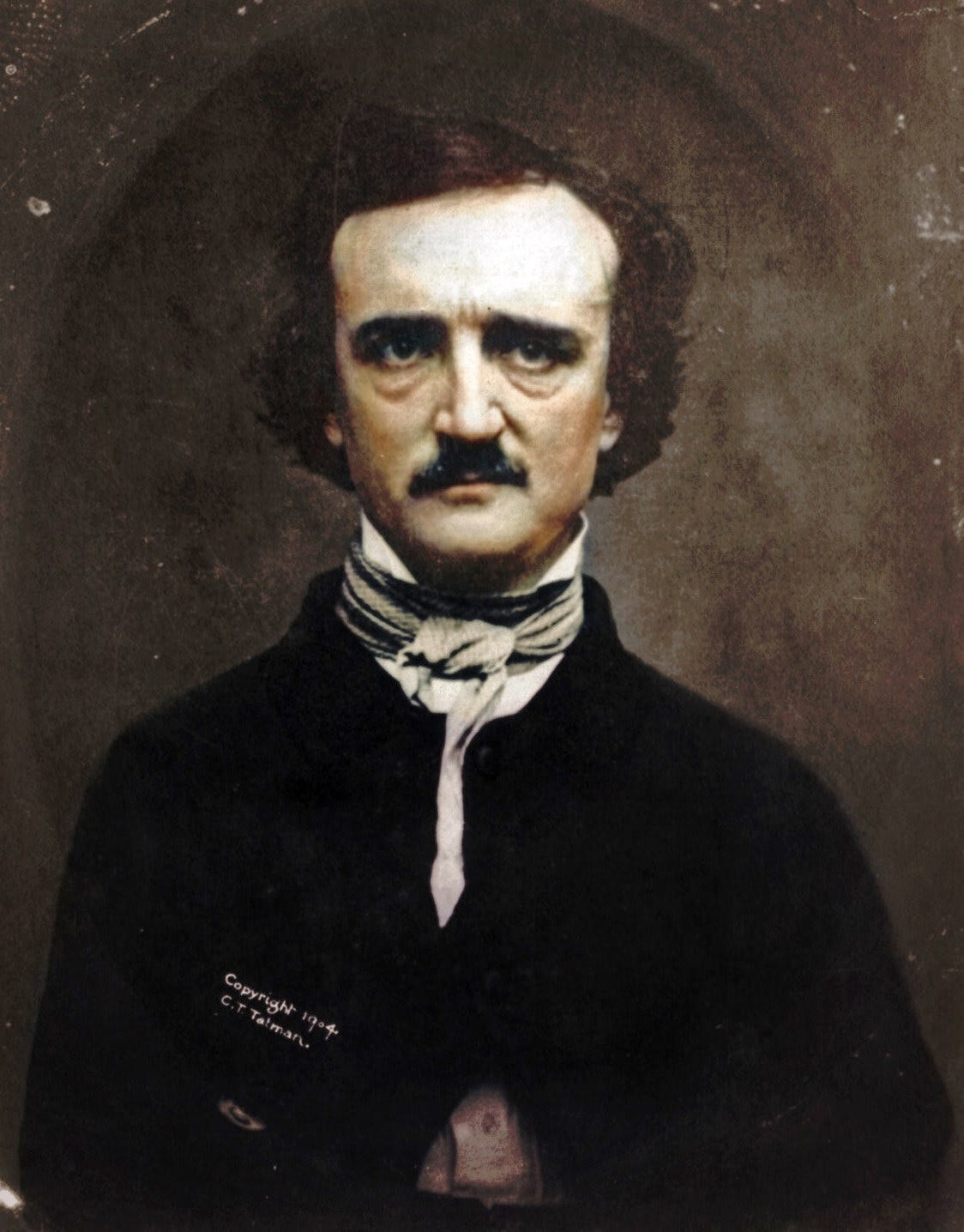

Well, that’s what happened to Edgar Allan Poe. The image we have of Edgar Allan Poe – drunken, dishevelled, tortured, mad – was largely created by Rufus Wilmot Griswold, a rival of Poe’s – both a professional rival and a romantic one – who became the literary executor of his estate after Poe’s death. Griswold spent the next eight years, which turned out to be the last eight years of his own life, doing whatever he could to drag Poe’s reputation into the dirt. In Griswold’s ‘Memoir of the Author’, published in his three-volume collection of Poe’s work, he claims that Poe “exhibits scarcely any virtue in either his life or his writings”. He takes great pleasure detailing long intoxications, conjuring images of Poe wandering the streets of Philadelphia in a drunken haze. He ends his singularly vituperative character assassination with these closing lines:

“There seemed to him no moral susceptibility; and, what was more remarkable in a proud nature, little or nothing of the true point of honor. He had, to a morbid excess, that desire to rise which is vulgarly called ambition, but no wish for the esteem of the love of his species; only the hard wish to succeed — not shine, not serve — succeed, that he might have the right to despise a world which galled his self-conceit.”

When I came to write my text game Evermore: A Choose-Your-Own Edgar Allan Poe Adventure, I had this image of Poe in my head as a tortured genius, a troubled and troubling alcoholic who confessed his deepest and darkest impulses upon the page. And, of course, there are aspects of Poe’s life that are troubling to modern sensibilities. Indeed, were met with disapproval during his own lifetime. Poe was 27 when he married his 13-year-old cousin, Virginia Eliza Clemm. There is nothing to suggest that the relationship was sexual – indeed, Poe often referred to Virginia as “Sis” or “Sissy” and she, for her part, seems to have encouraged his courtship of other, older women. Additionally, Poe did struggle with alcoholism, which cost him work and, sometimes, the esteem of his peers.

The images that I had from Poe’s writing in my imagination when I started writing Evermore were some of the most iconic and gristly in the writer’s catalogue: A dead man’s heart heard beating beneath the floorboards in The Tell-Tale Heart, a raven infernally and eternally calling the name of a lost beloved, a human chandelier formed of a king and his courtiers covered in tar and feathers and set, screaming and wailing, alight in Hop Frog, a man bricked up behind a wall and left to die in The Cask of Amontillado, the ash-black silhouette of a cat’s corpse pointing the way to the gallows in The Black Cat, a woman entombed alive in The Fall of the House of Usher and Berenice. These are lurid Grand Guignol images, some of which I had encountered in the remarkable 1995 PC adventure game The Dark Eye by InScape, in which Poe’s characters are animated as eyeless stop-motion puppets.

Indeed, many of the most famous film adaptations of Poe – such as those directed by Roger Corman in the 1960s – House of Usher (1960), The Pit and The Pendulum (1961), Tales of Terror (1962), The Premature Burial (1962), The Raven (1963), The Haunted Palace (1963), Tomb of Ligeia (1964) and the same year’s Technicolour phantasia, The Masque of the Red Death – many starring Vincent Price – use Poe’s tales as gothic jumping off points, taking images and scenes from the stories, but filling in the narrative details. Italian Poe adaptations, like Margheriti and Corbucci’s Danza Macabra or Castle of Blood from 1964, the omnibus film Tre passi nel delirio, Spirits of the Dead, one part of which was directed by Fellini, or Fulci’s infamously gory 1981 film of The Black Cat, are even looser, often sharing little more with Poe’s originals than a title and some motifs.

Perhaps the culmination of this tendency is the enjoyably stupid and often jaw-droppingly ludicrous 2012 John Cusack vehicle The Raven, which casts Cusack as Edgar Allan Poe himself, but inexplicably in the role of his fictional detective Le Chevalier C. Auguste Dupin, as he tracks down a murderer who kills in baroque set-ups taken from Poe’s own stories.

To tell the truth, I had only watched some of these. The Poe adaptations that made the greatest impact upon me and which I still believe are by far the most effective, were the two directed by my favourite Czech Surrealist, Jan Švankmajer – The Fall of the House of Usher in 1980 and The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope in 1983. The Fall of the House of Usher is a story about two men and a seemingly dead woman. One man is visiting, having passed on horseback “a singularly dreary tract of country”, the house Poe describes as a mansion with “bleak walls” and “vacant eye-like windows”. This house belongs to Frederick Usher, tortured and sleepless, given over to long flights of fancy. The dying and, later, seemingly dead and buried woman, is his beloved sister Madeline, “his sole companion for long years”. As the mind of Usher falls apart, so too does the house, split by a bolt of lightning in a zig-zag crevice from its roof to its foundation. Švankmajer tells this entire story without any human actors at all, instead focusing upon the eerie and dilapidated objects of the house, chairs which seem to carry the imprinted memories of their owner, the churning mud of the mansion’s grounds, which Švankmajer himself animated by hand. The effect is disquieting and uncanny and captures the weird animism present in the story, by which Poe writes of Usher’s belief in “the sentience of all vegetable things”.

Švankmajer’s adaptation of Poe’s The Pit and the Pendulum, which he combines with Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam’s French symbolist story A Torture by Hope, is more disturbing still. It is told entirely through the point-of-view shots of a man tortured by the inquisition. In some shots we see his hands grasping desperately before him. In the first half of the film, the man lies prone upon his back, staring up at a ghoulish grinning mural of a skeleton, a pendulum swinging and descending from just below its own mouth. Using rats to help chew through his bindings, he finds that the walls are closing in on him. The walls are decorated by Švankmajer’s late wife Eva Švankmajora with pin-joint figures in a Medieval diorama of pain and suffering. Behind these images of Hell real fire burns, making the walls scolding to the touch. The man manages to halt the infernal mechanism but, just as it seems he will escape, he is recaptured, presumably only to be tortured once anew. It is a profoundly pessimistic vision of the inescapability of human suffering and we might assume this pessimism to be Poe’s own, tortured by the early death of Virginia in 1847 at only 27-years-old, tortured still more by his fears of living internment in the grave, of being buried alive inside a coffin – a phobia that has very real cause behind it in the 19th century when people could still be buried with a rope inside their coffin to ring a bell to alert passers-by to their slow suffocation.

However, reading Poe at length – almost all his published fictional work – I discovered a Man of Letters, who was as much a humourist and a prankster as he was the miserable drunk characterised by the jealous and bitter Griswold. In 1844 Poe published a series of articles in the New York paper The Sun detailing Monck Mason's voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in only three days in a hot air balloon. Two days later, the story was revealed as a hoax. A year later, in 1845, The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar, the story of a hypnotist who speaks to a dead man under a mesmeric trance, was printed as factual reportage. In terms of horror precedence, it is hard not to think of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’s opening claim that “film you are about to see is true” or, later, the missing posters put up for the cast of The Blair Witch Project, with their IMDB pages listing them as dead. However, there is also a playfulness here. Poe was playing games with his readers. For instance, in The Gold-Bug, from 1843, Poe’s characters search for hidden gold, its location determined by a cryptogram solved with a simple substitution cipher. Readers has been encouraged by Poe a few years earlier to mail their own cryptograms to Alexander's Weekly Messenger, claiming that he would be able to solve any of them.

Some of the Poe’s stories are effectively shaggy dog stories, the kind of long-form groaners that your uncle might tell you. The Spectacles, from 1844, is essentially a terrible, terrible joke, about a short-sighted man who falls for who he believes to be a beautiful young woman across the room from him in an opera house. They get engaged and, by-and-by, his gets himself a pair of spectacles whereupon – horror upon horror – his betrothed is revealed to be eighty-two years old. It’s a tired, sexist joke and it’s also – importantly – very silly. This silliness is not what I expected to find in Poe, but it crops up again and again.

Yes, the Cask of Amontillado, is about a man bricked up and left to die behind a wall. But he also spends much of the story before this point, hiccupping. Which Poe spells out phonetically every single time. Originally the bird in Poe’s famous poem was not going to be a raven, but a parrot. The Tell-Tale Heart is a chilling story of obsession, voyeurism and bloody murder, but its opening lines are also… kind of comedic. “True, nervous, very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am, but why will say that I am mad?!” Well, to be fair… you do sound a little mad. Steven Berkoff’s famous performance of the piece is disturbing, but in playing up its grotesque elements, he also makes it funny.

Indeed, I think that’s what H.P. Lovecraft, who idealised Poe’s writing, got wrong about Poe. Lovecraft, a paranoid recluse, took his writing very, very seriously. His purple prose and snatches of Latin or Greek are not just intelligence signalling, but his attempts to live up to Poe’s style. But Lovecraft, like many conservatives, traditionalists and, yes, racists, lacked a sense of humour about himself. Lovecraft would not have written a story like Poe’s The Man That Was Used Up. In that 1839 story the unnamed narrator is due to meet the great Brevet Brigadier General John A. B. C. Smith. General Smith, a hero of the American-Indian Wars, responsible for the deaths of many Native Americans. Poe, of course, died a full decade before the American Civil War but as an unreconstructed man of the South, would have been an unlikely abolitionist. However, when the narrator of the story finally meets Brigadier General John Smith, what he finds is the ludicrous punchline to a joke – a bundle of clothes and prosthetics that has to make itself up into a man, little more than a talking severed leg. A grim, perhaps offensive joke, but a joke nevertheless.

Poe’s grimmest extended joke comes in the form of a parody. A Predicament was originally titled, tellingly, The Scythe of Time and is a grotesquely exaggerated version of the gothic tales published by the likes of Ann Radcliffe, Nathaniel Hawthorne and the writers of Blackwood magazine’s tales of sensation. Indeed, A Predicament was published alongside a piece called How to Write a Blackwood Article, just in case the parody was not already clear. In A Predicament, a woman, Signora Psyche Zenobia, walks with her poodle and servant into a large Gothic cathedral. Climbing the steps up the steeple, she pokes her head out through an opening to look out upon the city. Unbeknownst to her, however, the window is an opening in a giant clock face, in which her head is now stuck. The clock’s minute hand slowly, horribly, digs into her neck until it decapitates her, popping out one of her eyeballs with the pressure. Her head rolls down the street, her headless body staggers off, and a giant rat devours her poodle. This is the kind of hallucinatory set-piece you’d expect to encounter in a giallo film by Dario Argento or, with the flesh-eating rat, Lucio Fulci.

It is gruesomely funny and genuinely disgusting. In Poe, things are funny, until they’re not. For a writer with such formal command of language, Poe will happily push proceedings into area of extreme bad taste. It is this combination of the chilling with the ludicrous, the horrible with the fantastic, that I think Poe has the largest legacy upon horror cinema, outside and beyond of the gothic influences of his forebearers. Perhaps you wouldn’t have classy gothic films like Jack Clayton’s The Innocents or Robert Wise’s The Haunting without Poe, but neither would you have splatter comedies like Peter Jackson’s Braindead or Diablo Cody’s Jennifer’s Body. For that matter, I’d argue that Stuart Gordon’s and Brian Yuzna’s Re-Animator is closer to the spirit of Poe than it is to H.P. Lovecraft.

Hopefully this essay has introduced you to a side of Poe you might not have encountered before. If you want to explore his work further, please do take a look at my massive branching Choose Your Own Adventure hypertext game, Evermore, as well as a video lecture I gave on the making of the game, which contains a bibliography on Poe I have also drawn on here. Thanks for reading.

Gonna have to check out those Švankmajer films! They sound great.