Nope (2022), Werner Herzog, and Climate Change

On the Society of Spectacle and the Difficulties of Climate Activism

“See the animal in his cage that you built. Are you sure what side you’re on?”

(Nine Inch Nails, 'Right Where it Belongs')

CW: Reference to the Holocaust and racial exploitation, including PETA’s tendency to equate factory farming with both.

—

You are ten years old watching an acrobat in a red and gold sequinned leotard balance standing upright upon a horse’s back as it trots around a tiny circus ring on a village playing field.

You are younger – four or five – sat on the little plastic orange chair inside a Sainsbury’s shopping trolley pushed by your mother as you happily scoop out and consume the soft innards of a French baguette before it’s even been paid for.

You are in Sixth Form – seventeen or eighteen – watching, awed, the footage from Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982) in which a steamboat is pulled over a mountain.

The problem with bread and circuses under late-stage capitalism, is that sometimes the bread tastes really good and the circuses are really diverting and the spectacle up on the screen is really spectacular.

"Bread and circuses" – a phrase referring to the superficial distractions provided by a government to keep the people sedated and complacent – comes from the Roman poet Juvenal. The phrase is an example of a specific kind of a metaphor called metonymy in which the example given by the metaphor stands in for a broader tendency or practice. Metaphors tend to obscure the signifier – the image being used – in favour of the signified – the underlying concept represented by the metaphor. Metonyms, however, keep a certain emphasis on the signifying things themselves in their concrete everydayness. The Marxist comedian Mark Steel points out that when Karl Marx referred to religion as “the opium of the people” his point was not that religion was a brain-benumbing evil, but that “religion, like other ideas, is a product of the environment” [1]. When a homeless person is shivering with cold as the rain pelts down, feeling completely alienated from a society that largely chooses to ignore and pity them at best—or abuse and ridicule them at worst—it makes sense that they would turn to the euphoria of heroin, however devastating the long-term consequences, following from their material circumstances logically and sensorially. Taking Marx’s statement as a metonym rather than just a metaphor, means that before we get to thinking about religion, we can’t pass over the ‘opium’ part of the quote as a mere placeholder for addictiveness, but attend first to //how and why// opium is addictive and //in what circumstances// people find themselves addicted to it.

Likewise, we shouldn’t forget when we use the phrase “bread and circuses” to refer to cynical tabloid baiting from a populist party, how nourishing bread can be when starved and how entertaining and diverting a spectacular performance can be when the audience is worried, anxious and stressed.

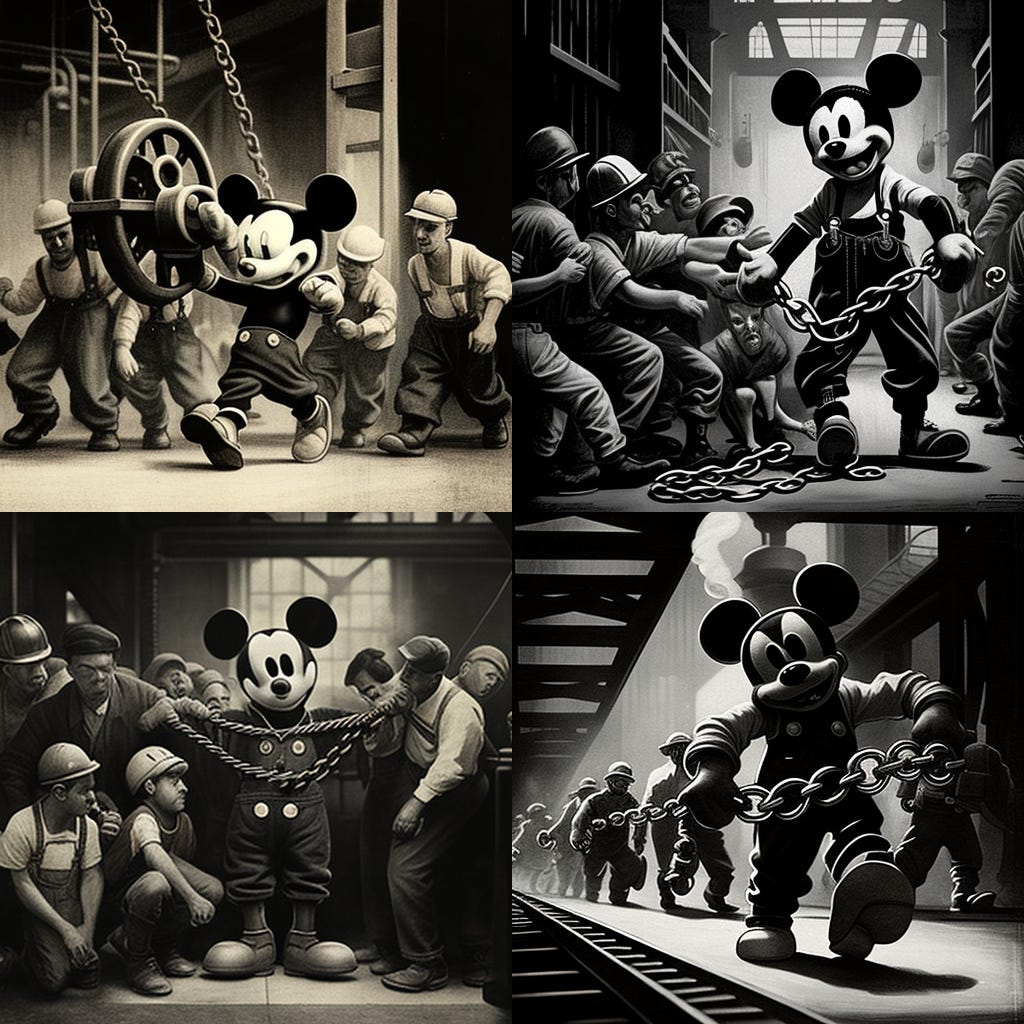

Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein never forgot this when writing about the appeal that Mickey Mouse held for the American public at the dawn of the 20th century. Far from being contemptuous of the appeal that Disney held for Americans, he wrote sympathetically that “Disney is a marvellous lullaby for the suffering and the unfortunate, the oppressed and deprived” [2]. Like Marx writing about religion before him, Eisenstein wasn’t being sarcastic. The plasmatic freedom of Mickey Mouse was a near-spiritual release for workers suffering through long, monotonous days in factories and offices, chained to rational clock time as inexorably as Mickey was not.

In Suburban Fantastic Cinema: Growing Up in the Late Twentieth Century, Angus McFadzean makes much the same point about the films of Steven Spielberg for the Millenials who grew up with them – that they provided a therapeutic experience for children growing up within a neoliberal society.

However, while Eisenstein saw the therapeutic quality of Disney precisely in its aesthetic difference from life under capitalism, McFadzean – writing a century later – sees Spielberg’s cinema as being therapeutic due to its mirroring of the experience of life under late-stage capitalism. He argues that Amblin Entertainment’s films provided a “unique combination of terror with wonder” which captured and reflected back to the audience “the feeling of this new hyper-accelerated turbo-capitalism” [3]. McFadzean isn’t even being critical of the genre, but largely affectionate, when he writes that “suburban fantastic cinema is a space in which audiences can relive the exhilarating and un-nerving process by which their imaginations and their identities have been commodified and consumed” [4].

In Wim Wenders’ fascinating 1982 documentary Room 666, Wenders set up a camera in room 666 of the Martinez Hotel and interviewed directors present at that year’s Cannes film festival [5]. Present was Steven Spielberg [5] who was just about to about to release E.T. (1982), which would very shortly become the highest grossing film of all time. Justifying his approach to filmmaking within the American studio system, Spielberg explains to Wenders (unseen behind the camera): “Everybody wants to be a hero and […] everybody wants that hit to be a $100 million hit”. He seems simultaneously exhausted by this pressure and confident in the knowledge of his ability to live up to it.

Wenders also interviewed Werner Herzog. Similarly confident but far more at ease than Spielberg, Herzog is only ready to answer Wenders’ question about the state of the cinema once he has comfortably removed his shoes and socks, and turned off the hotel television that had been left broadcasting to the back of his head. In a very similar vein to his opening words in Les Blank’s Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (1980) Herzog – perhaps channelling Robert Bresson – speaks of the need of creating necessary images, images adequate for the civilization which has produced them. While Herzog is too atheistic to refer to such images as ‘holy’, he clearly means for them to be transcendent, rising above the image-noise of the banal and televisual. A long shot of a boat going over the mountain. A black-and-white image of an acrobat swinging in a trapeze as though suspended in mid-air [6]. A close-up of a hunk of bread passed around in Communion [7] – not holy as the body of Christ but because it is a necessary, nourishing substance both in and of the world. Producing these cinematic images within what Guy Debord describes as ‘The Society of the Spectacle’ [8] runs the risk of the adequate images spoken of by Herzog being immediately commodified into a shallow spectacle, a mediated representation always already severed from authentic experience.

Today, when we can visit Google and see the image of Herzog’s boat being pulled over a mountain as an animated gif [9] we might call this process memeification.

Werner Herzog was originally written by Jordan Peele to play the part of the legendary fictional cinematographer Antlers Holst in his neo-Western science-fiction horror blockbuster Nope (2022). In the film, siblings Otis "OJ" Haywood Jr. (Daniel Kaluuya) and Emerald "Em" Haywood (Keke Palmer) recruit Holst to photograph an alien being hovering in the sky near their ranch because they know he is driven to get the “impossible shot” – a shot perhaps equivalent to Herzog’s civilisation-adequate images, like Fitzcarraldo’s boat. In the event of the film, Holst is played not by Herzog but by a grizzled Michael Wincott.

A lot of reviews of Nope appreciated Peele’s direction, but found his screenplay muddled, lacking a unifying message [10]. While I personally prefer a multivalent, unresolved, and ambiguous allegory (as per the films of David Lynch) to a heavy-handed, singular, biblically self-important allegory (as per the films of Darren Aronofsky), I also think that knowing that Werner Herzog was intended to play Holst goes some way to clarifying the themes of the film. I will attempt to do this via four references to Herzog’s filmography.

The first reference – to Grizzly Man (2005) – is one that other reviewers who have picked up on Holst’s connection to Werner Herzog have already made. Michael Shindler in the conservative publication The American Spectator argues – confusingly to my mind – that Nope is inherently reactionary due to what he perceives as its condemnation of Hollywood spectacle [this from the political movement that brought us Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump]. Shindler contrasts the fortune-seeking OJ and Em unfavourably with what he perceives to be the integrity of Antlers Holst, who he recognises as an avatar for Herzog. Herzog, claims Shindler, respects “the taboo” of spectacle, choosing in Grizzly Man to forgo showing the soundtrack recording of conservationist Timothy Treadwell eaten by bears due to – as Shindler reads it – a desire not to exploit the footage for spectacle [11].

Shindler, however, misses the more essential connection between Timothy Treadwell and the character of Steven Yeun’s Ricky "Jupe" Park, explained by Reddit user Eeststreatdrug [12]. Jupe was a child actor on a ‘90s daytime sitcom called Gordy’s Home, featuring a suburban family and their lovable pet chimpanzee. One of the chimps who played Gordy – stressed and seemingly triggered by the sudden explosion of a balloon – suddenly turned aggressive, mauling the face of one of the other child performers in front of the traumatised Jupe. In the years since, this incident has become an urban legend, with Jupe making money through memeifying his part in proceedings, charging visitors to his Western-themed amusement park to visit a room full of Gordy’s Home memorabilia. In an uncanny mirroring of his response to this past trauma [first as tragedy, then as farce, to paraphrase Marx] Jupe gets embroidered in the exploitation of another wild animal performer – only this time it’s not a chimpanzee, but an alien. Rather more culpable as an adult than as a child, Jupe makes money through exhibiting this alien (later named Jean Jacket), which is eventually triggered by the exploding flash bulbs of phone cameras to "go ape" and devour Jupe, his family, and all his employees.

Eeststreatdrug’s whole comment should really be read in full, but the most important point he makes is that Jupe and Treadwell “were both eaten by the thing they were attempting to tame and exploit” and that “like Gordy and Jean Jacket, the grizzly was not being malicious in a human sense, but was just an animal following its instincts in an unnatural situation”. The otherness of animals can be met with respect but can also register as a kind of absurdist horror. Herzog is on record multiple times as finding chickens to be existentially blank creatures, seeing them as possessed of a kind “of bottomless stupidity, a fiendish stupidity” [13]. In the final shot of his 1977 film Stroszek – one of his few films to be primarily concerned with America’s ‘Society of the Spectacle’ – a chicken trapped in glass-fronted arcade booth dances repetitively for chicken feed. It is one of Herzog’s “pure and absolute images that reflect our civilization as a whole” [14]. The chicken’s black beady eyes reflect our own alienation back at us – as we too are stuck in our glass cages performing repetitive gestures for chicken feed.

Indeed, if we’re really keen on pushing the philosophical boat as far up this particular mountain as it can go, we might reflect that such inane meaninglessness is the ultimate condition of the universe – nay, even existence itself [15]. As a commentator on Freddie deBoer’s Substack replied to deBoer impressing upon them the need, par Albert Camus, to “imagine Sisyphus happy” – pointlessly pushing and heaving his way up that mountain for all eternity with a smile upon his face… we don’t have to imagine that [16]. In the face of the deathly pointlessness of existence we may opt for bathos rather than pathos. We might decide that the humble dancing chicken is a rather more apt metaphor for our existential situation than the decidedly more spectacular mountain-defying boat.

This is why, in Nope, when Antlers Holst witnesses the spectacle of a desert landscape demarcated by wavy-armed inflatable tube men, he not only sounds gnomically profound as he asks whether the others have ever seen anything so stupid, but also says it with a laugh.

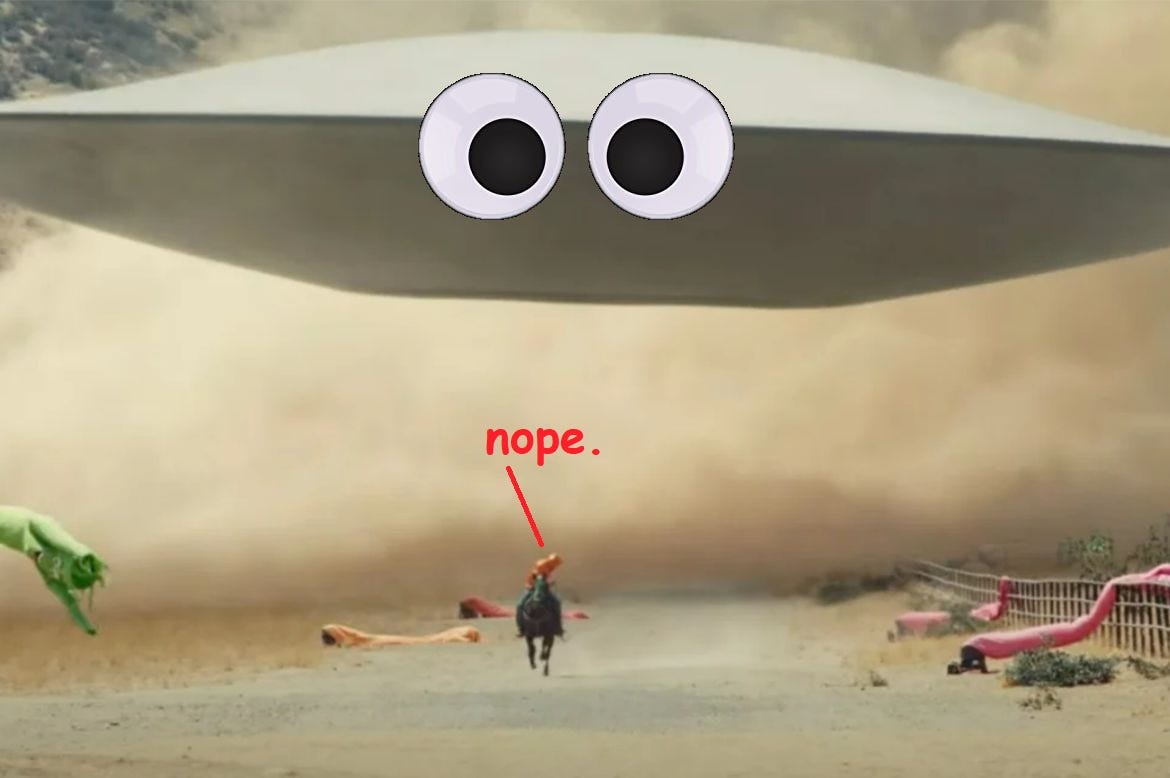

The air dancers in the desert are as existentially stupid as Herzog’s chickens, but that gives them a kind of existential purity. We can’t compute such imagery in a logical or sensible way, our brain just bounces off it. We are left instead with holy laughter. The same happens with Jean Jacket, the alien. As viewers we spend the first half of the film assuming that Jean Jacket is a futuristic UFO. The fact that the end of the film reveals that what we took to be a UFO is actually the alien itself… and that, furthermore, the alien is as much of a flat-brained predator as Spielberg’s Jaws or the T-Rex from Jurassic Park (1993) [or, indeed, the heavy-duty lorry from 1971’s Duel]… is as much of a cosmically funny punchline as it is a twist.

In the profoundly stupid fate of Antlers Holst we find another Herzog reference. In his bid to get the “impossible shot”, Holst makes his way to the top of the hill when he fully anticipates he will be swallowed up by the angry and ravenous Jean Jacket. As he is sucked up into the alien’s gaping black (and weirdly square) maw he continues filming, documenting the moment of his own demise. For me this immediately recalled Herzog’s plan to be blown into the air by the erupting volcano he sought to document in La Soufrière (1977). Interviewed by Paul Cronin, he told Cronin, that he – and his cameraman Ed Lachman – had left a camera in the far distance of the volcano that would take single frames throughout the day of the anticipated explosion so that there would be some footage of him being blasted airborne [17]. If we take Herzog at his word that he was neither being a daredevil nor suicidal, then I think we can say that he was not taking the prospect of his own death very seriously. This speaks not not just an non-anthropocentric impulse in Herzog’s filmography, but an even deeper, stranger impulse to not elevate what we recognise as living beings above non-living ones. If, at the heart of Herzog’s romanticism is a rejection of Enlightenment values and its civilisation [18] then this rejection includes the long legacy of the pre-Enlightement concept of the Great Chain of Being and all the clarificatory systems that so followed, valuing organic life over non-organic. A volcano is no less sublime by virtue of its potential to kill a single human being called Werner Herzog [19]. Likewise, for Antlers Holst, the alien/ Jean Jacket is no less sublime for abducting and consuming him.

Finally, the Herzog film most relevant to Nope is – upon the surface – perhaps his least essential, his 2012 documentary of Las Vegas band The Killers, funded by American Express. The film climaxes at a gold mining themed adventure park some twenty-five minutes from the Strip, cut into the mountains. Herzog playfully teases the band members about the inauthenticity of the park and of Vegas itself, with Brandon Flowers replying that, “We didn’t know that it was strange to other people until we went to other places... I’d never looked at it that way... that it was fake or a facade”. Herzog then shoots Flowers stood in front of an animatronic cowboy which pretends to play a guitar while Flowers stands there looking uneasy. He holds the shot without Flowers talking for a full thirty seconds.

I have watched this shot more times over the last decade than would be prudent of me to admit. Far, far more than the rhapsodic shot of the wind blowing through the field of barley at the start of The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser / Jeder für sich und Gott gegen alle (1974) or of the haunting and terrible musical act (a brothel singer and its matron) that interrupts the long tracking shots of the desert in Fata Morgana (1971) or the nightmarish oil well in flames from Lessons of Darkness / Lektionen in Finsternis (1992). These shots stir and provoke the soul far more than Brandon Flowers’ face ever could… and yet it is that face I always return to. Do I see something of my own expression in that face? Confused and unsure what to say or do when faced with the terrible, absurd impasse that a world ruled by mechanical cowboys has brought us to?

When OJ is in his car and Jean Jacket is in the sky above like a harbinger of the apocalypse he tries to do something – to open the car door – but he can’t bring himself to react. His brain won’t comprehend the immensity of the threat that he faces. “Nope” he says to himself, ducking out of confronting the situation.

Nope.

A children’s amusement park of mechanical cowboys is the central location of Nope, the site where Jean Jacket, the alien, is exhibited nightly to paying visitors by Ricky "Jupe" Park; the site where he also keeps his shrine to Gordy’s Home. The park is called ‘Jupiter’s Claim’ and it has its own Alternate Reality-style website (made to promote the film). The website, quite brilliantly, is an empty shell of razzle-dazzle graphic design thinly papering over dead links, out of stock merch items and ‘Under Construction’ pages. The main interactions resemble the "clicker" games that hook players into mini feedback loops Skinner box-style, satirised a decade back in Ian Bogost’s notorious Cow Clicker, which anticipated the ever more exploitative micro-transitions and loot crates of modern gaming.

The website is a perfect match for ‘Jupiter’s Claim’ since, as Britt Hayes writes in a barn-stormingly brilliant article on Nope, “For Ricky […] exploitation is the natural way of things. As a child star, exploitation was presumably modeled for him by greedy parents; in turn, and with no other effective coping mechanism, he exploited his own trauma for profit. Now, Ricky makes the fatal, hubristic error of believing—as the chimpanzee’s trainers did—that he can control and exploit an alien species” [20].

Every so often the website starts to crackle with static electricity, the triumphant Western background music stops looping, and the skies above the park turn dark. Ricky believes all he is selling is spectacle, but the spectacle is exploitation. Britt Hayes explains:

Ricky’s other critical error also happens to be one of the few indicators of his humanity: mistaking exploitation for spectacle. In this, at least, Ricky is hardly to blame. The two words have become increasingly interchangeable in both film and social theory […] Exploitation has become the predominant language of America. And maybe we shouldn’t be surprised, given that it feels like the only way to have a chance at accumulating wealth in an extreme capitalist society […] Perhaps that’s why Nope’s Ricky is compelled to turn the alien of mass consumption into an attraction. His childhood trauma has steadily decreased in value and Ricky’s attempt to capitalize on his name with a lazily-conceived theme park isn’t exactly a success. When we have nothing left to exploit in ourselves, we exploit others. [21]

Extinction Rebellion, as an activist group, made its name off spectacle. As with Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, one of its most notable feats of spectacle came through placing a big boat where it seemingly should not be – in Fitzcarraldo, halfway up a mountain; for XR, in the middle of Oxford Circle.

I spent a night underneath the pink boat, occasionally venturing forth a few metres in the early hours of the morning to debate climate change and XR’s tactics with drunk/ coked-up young bankers and businessmen returning from the nights out in Oxford Circus. When XR Ipswich put on a protest some months later in December 2019 we dropped a huge banner from the Noah’s Ark docked outside the University of Suffolk, reading, “We need a better plan than this”:

December 2019 was almost three-and-a-half years ago now and it feels like a lifetime past. There was a flinty sense of hope in that first year of XR activism. This was before the first UK lockdown and just before the devastating Australian bush fires of 2020.

Extinction Rebellion still exists as a group, but on the very last day of last year they released a statement saying XR would be stepping away from mass disruptive actions like the one that saw the pink boat air-dropped into London. The group stated, “As we ring in the new year, we make a controversial resolution to temporarily shift away from public disruption as a primary tactic” [22]. With respect to XR as a group, they lasted four years doing these kinds of actions. I only lasted the first two of those years.

Partly the reasons for this were personal. With Brexit looming and Priti Patel’s Police Bill making its way through the courts, my partner and I decamped to the Netherlands (where it quickly became apparent that we were never going to get hired for even the most low-paying of jobs) while Covid-19 meant that XR’s activism shifted online. However, after the bleak farce of the September 2020 London protest (in which we were given permission to protest on Parliament Square and then summarily kettled) I started to lose faith in the two main kinds of protest in which we were engaged, e.g.

1.) Theatrical protests like the boat actions above. These are spectacle. Spectacle dulls the mind and is consumed rather than critically engaged with. Most problematically it creates an division of "us" (the protestors) and "them" (the observers) and vice versa. People watching such a protest from the outside rarely think “how can I get involved?” but take photographs and videos which they then post on social media. Theoretically this works as "awareness raising”, but does raising awareness change material circumstances or even motivate the individual to make changes? I am aware of the occupation of Palestine and the suffering of oppressed Palestinians. This awareness does not save Palestinian lives. Ultimately (and, perhaps, wrongly) it does not feel like "my" fight and so I watch from the sidelines and shake my head and sometimes shed tears and occasionally donate money to what seem to be useful grass roots charities. As with recycling our plastic bottles, this will not change systematic injustices or the suffering that bleeds out from such injustices.

I have, perhaps, become cynical about this awareness raising as a tactic due to the inability of mass awareness raising campaigns across the last decade to improve rates of mental illness among the youth or support and understanding for the most marginalised of the mentally ill [23].

2.) Disruptive protests like the road blocks and the misguided London underground protest which led to protestors being pulled down from the tube trains and beaten up to very little public sympathy. One of the key philosophical ideas behind this tactic is that when the public see the police pepper spraying and beating and arresting and generally mistreating protestors and teenagers who ultimately just care about sustaining the continuation of life on Earth they will react with outraged sympathy and demand the systematic change the protestors are asking for. Bugden’s 2020 study ‘Does Climate Protest Work? Partisanship, Protest, and Sentiment Pools’ for Socius suggests that civil disobedience can achieve this… but only in groups that are already in alignment with the ideals of the protestors [24].

As a member of XR Ipswich I took part in two notably disruptive protests, both involving occupying and thus shutting down the court of a petrol station. During the first action at a BP petrol station I took on the role of a public liaison officer. In short, I was the person who spoke calmly and apologetically to motorists and informed them that they were not going to be able to purchase their petrol from that particular BP station that day. In doing so, I explained that BP have a history of devastating oil spills and safety lapses, committing industrial-scale bribery and complicity in the torture and murder of environmental activists. We had deliberately staged the protest at a BP petrol station that happened to be opposite a Tesco petrol station so that car drivers would not be unduly inconvenienced by the protest.

Car drivers acknowledged and agreed that BP were corrupt. They knew about the oil spills. They said they agreed with the principle behind the protest. But, they said, they still wanted to purchase BP petrol. BP petrol was, mile for mile, cheaper than Tesco’s and they wanted to employ their freedom of consumer choice. This kind of language was used. As the day wore on and I spoke to more and more motorists it became increasingly apparent that individual consumer choice was really, deeply emotionally and psychologically important to a lot of people.

And… honestly… who could blame then? In a country where we have an archaic electoral process and where most of us don’t go to the schools and universities that most politicians go to; where many of us work tedious jobs we don’t want to work; where we are policed and surveyed and tracked and observed, our data harvested, our bodies funnelled and shunted by coercive architecture and narrow shopping aisles and escalators and elevators, all the while bound to the braying demands of our hungry, thirsty, tired bodies – being able to spend our hard earned money where we want to spend it is one of the only enjoyable freedoms left to us.

Unfortunately, sufficient action on climate change requires the government to drastically limit consumer choice. We cannot be allowed to fly where we want on holiday. We should not own private carbon dioxide emitting vehicles. We desperately need rationing on disposable consumer goods. But every politicians knows that such policies would be electorally disastrous. These are the things that keep most people’s heads above water. We can’t be expected to be miserable and do without the dopamine-triggering trinkets that get us out of bed in the morning, let alone the objects like cars that many people depend on to get to work, and the holidays that get then through another month of the soul-destroying labour they perform once they’re at work.

If I did not have access to the music I love and my library of Steam games and a rich selection of ethically-sourced chocolate I probably wouldn’t get out of bed either. I don’t live in a society that provides a lot of free, communal pleasures. The alternatives outside of the algorithms seem like slim pickings… requiring a lot of energy (gardening! exercising! writing!) that I often don’t have after a long day of work. And I have worked in far more draining jobs than teaching! When I worked in insurance I could barely watch Britain’s Got Talent, let alone a Werner Herzog film! If a climate protest had disrupted my bus journey home back then I probably would have been angry. My inner resources were already stretched very thin.

So, how does this relate to Nope?

In the face of the alien threat of Jean Jacket, do the siblings band together with their community to mount a heroic resistance? No. They mostly spend a long time circling the question of whether the thing actually exists or not while trying to get on with their lives. When they accept that it is real they buy a lot of stuff. Because this is what we who live in capitalist countries do to make ourselves feel more safe and secure. How many preppers actually spend their time learning (not from a book, but in the woods) how to hunt without a gun and find water sources… and how many spend their time online on prepper communities comparing notes on which telescoping magnetic pickup tools, solar charges and water filters to buy?

The main characters in Nope don’t buy survivalist tools when the shit hits the fan, they buy filming equipment. Partly this is because Jordan Peele is a filmmaker and this is likely what he spends money on to orient himself in the world; however, in terms of the plot, this is because Em and OJ want to document the alien. Em, in particular, wants to sell this footage to Oprah. She wants to exploit this unknowable other as a commodity… just as white Europeans did to Black persons in the exoticizing travelogue and ethnographic films of early cinema [25]. In doing this, she is just following the logic of capitalism. As the Salvage Editorial Collective remind us, “Accumulation is, for capital, an imperative and not an option” [26] and, in terms of late capitalism more specifically, “the dispersed, privatised accommodation and individualised transportation of modern life offer individualised, immediate-term and distinctively capitalist answer to specifically human strivings” [27]. Notably, Em immediately thinks of the photographs not in terms of any implicit value, but in terms of their exchange value, excitedly telling OJ about the imagined Oprah sale. Peele makes it easy to wonder whether Jean Jacket (disguised as it is, for much of the time, as a cloud) would be posing much of a threat to the human characters at all were it not for Ricky luring it out with horses as bait to be photographed by paying visitors to his amusement park (and then Em endeavouring to do much the same). Just as coal only poses a threat to humanity when transformed through human labour, Jean Jacket only starts to eat up humans when subjected to a process of value extraction. Like with Treadwell and his bears, if Jean Jacket had been left to its own devices there would have been no spectacle.

If Em is stupid in her approach here (and if I am stupid in my chocolate consumption and having worked in insurance and you, dear reader, are stupid in whatever particular ways you are stupid in) she is no more or less stupid than capitalism itself. As Sam Kriss and Ellie Mae O’Hagan argued back in 2017, when faced with climate change, “it’s not that, like Kafka’s heroes, we’re facing a vast and inscrutable apparatus whose operation seems to make no sense, trembling in front of a machine. What’s unbearable is that it does make sense; it’s the same logic that governs every second of our lives” [28]. It is then with considerable sympathy towards ourselves as a species that they write that “the first thing to go extinct from global warming was Aristotle’s rational animal. We do not think about things and then do them afterward; we do not think at all. We are plunging carelessly and catastrophically into a world created entirely by accident” [29]. While one might reasonable argue that the CEOs of Shell and BP and ExxonMobil knew exactly what they were doing (as did the guards of concentration camps or – from the perspective of a PETA supporter – the owners of factory farms) Kriss and O’Hagan counter that the suffering was never the point; everything was about the accumulation and the profit. Ricky doesn’t intend for Jean Jacket to suck up and digest a whole host of people… he wanted to extract profit from them. The suffering was the surplus.

When I finished watching Nope with my partner and some friends I immediately talked about it as though it were quite matter-of-factly an allegory for the human response to climate change (in the wake of our exploitation of the natural world). My partner didn’t agree with me whatsoever. I actually think this is what makes the film an effective allegory for climate change compared to the big climate change allegory film of the previous year, Don’t Look Up (2012), a film that simply did not work as a successful allegory for a lot of critics (even while it functioned as a semi-successful comedy). Ryan Meehan asserts that one of the central reasons Don’t Look Up fails as an allegory for how humanity (or America specifically) is failing to deal effectively with climate change is because a comet (the external threat in the film) makes for a wholly inelegant symbol for the threat of global warming. He writes that a “radically external event like a comet’s arrival from outer space […] bypasses altogether the complex interconnections that a warming planet shares with nearly every facet of waking life in the developed world” [30].

Technically this critique is also equally applicable to Jean Jacket if treated as an symbol for the threat of climate change (and it is by no means clear that Peele intended it as such). However, compared to a comet (which is just a bunch of ice and rock with a pretty tail of gas) Jean Jacket is multivalent, tentacular and weird.

To quote a tweet from Eric Roston, “climate change is weird because it simultaneously touches every part of life on Earth and still remains somewhat remote from the daily experience” of life [31]. This is why Timothy Morton calls climate change a “hyperobject” [32] – it is too temporally and spatially vast for us to grasp all at once. A comet is easy to get a handle on. Jean Jacket – by turns a cloud, a UFO with a square mouth, and a Georgia O'Keeffe painting of a jellyfish – not so much. This multivalence is what makes Nope a film that invites thought and curiosity, rather than leaving the audience feeling like they’ve been beaten over the head with smug liberal certainties as with Don’t Look Up. This makes for better art, but it also rings truer to most people’s experiences with climate change where they suffer the localised phenomena without grasping the vast thing in itself [33]. Also, because climate change is bound up with complex systems in which we are inextricably intertwined, the film simultaneously works elegantly as a critique of whichever of those systems the individual viewer feels most angry/ scared/ concerned about. So, Celia Mattison can write an article for Electric Lit about how the film perfectly captures the disappointment of the Biden administration, which is a reading that would not have occurred to this particular non-American viewer, while also striking me as emotionally convincing.

The complexity and multivalence of climate change (which necessitates the complexity and multivalence of any allegories that attempt to engage with it lest they end up feeling overly simplistic and moralising like Don’t Look Up) is partly due to the complexity and interconnectedness of the systems we have grafted onto and intertwined with already highly complex natural systems. It gives me a measure of steely comfort to read James Bradley’s reflection that “[s]ome studies […] suggest the complexity and interconnectedness of a society may – perhaps counter-intuitively – make it more, rather than less resilient”, instructing Australian policymakers to “listen more closely to Indigenous Australians, whose bonds of community and culture have enabled them to survive two and a half centuries of disease, dispossession and violence” [34].

Of course, developing resilience may come in the form of practising active resistance, as demonstrated in Daniel Goldhaber’s recent How to Blow Up a Pipeline (2022), based upon the 2021 book by Andreas Malm of the same name. By the end of Nope, Em, OJ, Holst and Angel Torres (Brandon Perea) have become something of an active resistance group, banding heroically together to stop Jean Jacket’s destruction (and capture it on camera). Notably, this is a Western, so our characters band together as a small-knit group of intrepid outsiders, not as community builders (or leaders). This is the role of a vanguard, but most of us are as yet unwilling to handle explosives and and ride horses and potentially get ourselves shot to save our communities.

Indeed, many communities will not be saved in the years and decades to come. Many societies are going to be strange and alien for those of us who survive. But love, wonder and even pleasure can persist amongst chaos and suffering… and most activities, people and things that provide us these nourishing emotions are not inextricably bound to capitalism nor to spectacle.

After the circus visit I described at the start of this article, the performers showed the kids of the village how to use the diabolos and spinning plates and other wonders, in exchange for which the kids of the performers attended the village school for the week they were there [35]. Bread can and is distributed through initiatives like Food not Bombs. While I’m not sure if anything can redeem the colonialist exploitation of some of Herzog’s filmmaking, he has produced other works featuring indigenous groups, like Ten Thousand Years Older (2002) about the Amondauas (Uru Eus) people of Brazil, which are far more respectful and far less patronising than the bulk of white European and American cinema about indigenous peoples.

As a protestor it is very tempting to keep those outside the protest at arm’s length and maintain an "us and them" dynamic. I remember on one protest we went on through Ipswich I was in charge of distributing leaflets. One of the other organisers became frustrated with me because instead of just handing out as many leaflets as I could, I would stop to talk to the members of the public I handed leaflets to. However, it was only through these moments of connection that they were whatsoever brought into the cause and the spectacle of the protest was punctured. One of my biggest regrets from my time in XR is not pushing further on an idea my partner had of volunteering to help people in our local community to garden as long as they agreed to allow a small portion of their garden to be rewilded. XR have often been criticised for being too white and middle-class (which is broadly true, though more so in some local groups than others, I found) but I think it’s central problematic has been a lack of community engagement.

Film is always going to be a medium of spectacle. That is why I am sceptical it can do much to address climate change and biodiversity collapse. However, the least a film can do (if it is dealing with topics like these) is to make its audience engage with its critical ideas and make them feel more inclined towards action and community engagement. The last shot of Nope is a spectacular Western-style shot of OJ/ Daniel Kaluuya on a horse, having returned triumphantly from subduing Jean Jacket. Importantly, this shot is from the point of view of Em. When OJ looks towards her, he is looking towards us, signalling with his eyes to our eyes, puncturing the spectacle and inviting us to look back and engage.

[1] Mark Steel, Mark Steel Lectures: Karl Marx, BBC, 2003

[2] Sergei Eisenstein and Jay Leyda (ed.), Eisenstein on Disney, 1986, p.3.

[3] Angus McFadzean, Suburban Fantastic Cinema: Growing Up in the Late Twentieth Century, 2019, p.39.

[4] Ibid., p. 125.

[5] Wim Wenders, Room 666 / Chambre 666, 1982

[6] Thinking not of Herzog, of course, but Wenders’ classic film of earthbound transcendence Wings of Desire / Der Himmel über Berlin (1987).

[7] Thinking of Robert Bresson’s ineluctable but crisply real imagery here, especially of hands, such as in Diary of a Country Priest / Journal d'un curé de campagne (1951). For Bresson as a Catholic Jansenist, unlike Herzog, the fact that the bread is – at the moment of Communion – the body of Christ, would be essential.

[8] Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle / La société du spectacle, 1967.

[9] Okay, I’ll fess up to having made the above gif. I find it interesting that such a necessary/ adequate image makes for such a bad gif!

[10] See, for example, Peter Bradshaw, ‘Nope review – Jordan Peele’s followup to Get Out and Us is a bit meh’, The Guardian, 10 August 2022; Troy Harwood, ‘Nope: Muddled allegories redeemed by spectacle, Australian Book Review, 16 August 2022; Steve Biodrowski, ‘Film Review: Nope’, Hollywood Gothique, 27 July 2022.

[11] Michael Shindler, ‘Jordan Peele’s Nope: The Reactionary Blockbuster of the Summer’, The American Spectator, 17 August 2022. I actually think this is a too charitable reading of Herzog’s intent who does, after all, film himself listening to the recording of Treadwell and his girlfriend being eaten – then telling Treadwell’s ex-girlfriend, “You must never listen to this”, before leaving her with the footage. Herzog may have wished not to sensationalize Treadwell’s death too much, but I suspect he also knew that what viewer would conjure in the minds might be even more impactful than if he’d played the recording.

[12] Eeststreatdrug, ‘Nope and Grizzly Man’, Reddit, August 2022

<https://www.reddit.com/r/NopeMovie/comments/wle0v6/nope_and_grizzly_man>

[13] This quote has been traced back to a 2014 Reddit AMA with Errol Morris and Joshua Oppenheimer, but I swear he said something very similar in the original 2002 edition of Paul Cronin’s Herzog on Herzog. Roger Ebert event quotes it in his report from Ebertfest 2007 where he also links back to a transcript of Ebertfest 2005 where Herzog is on about those adequate images again! Despite treating images with great seriousness and sactitity, Herzog is never above memeifying himself in interviews, playing the greatest hits, as here:

[14] Wim Wenders, Tokyo-Ga, 1985.

[15] Or so Thomas Ligotti would have it in The Conspiracy Against the Human Race, 2010.

[16] I believe it was 'KT' but I am happy to be corrected. He said something along the lines of “No I don't”.

[17] Werner Herzog and Paul Cronin, Herzog on Herzog, 2002, pp.149–50.

[18] This gets to the heart of how Herzog can be simultaneously Nietzschean yet anti-Nazi. I suspect that, for Herzog, the Nazis, with their “scientific” classificatory systems were as bourgeois as the Enlightenment-era liberals of The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974). There are few moments as worthy of contempt in Herzog's filmography as when the clerk happily witnesses Kaspar's autopsy and celebrates at the discovery of his enlarged cerebellum, “What a wonderful, what a precise report this will make […] Finally we have got an explanation for this strange man”. Herzog's failure (or refusal?) to fully extricate his work from the Romantic Sturm und Drang elements of Nazism is what has led to much of the criticism of his 2022 novel The Twilight World.

[19] And his crew and the other remaining inhabitants of Gaudeloupe.

[20] Britt Hayes, ‘Two: It's Alien. Three: It's exploitation’, Monkey Paw Productions, 5 August 2022.

[21] Ibid. Seriously, read Hayes’ article above. This article is just a sequel to it.

[22] Extinction Rebellion, ‘We Quit’, 31 December 2022.

[23] Freddie DeBoer is a particularly fierce and trenchant critic of this, such as in, ‘The Gentrification of Disability’, Substack, 23 May 2022 and ‘The Incoherence and Cruelty of Mental Illness as a Meme’, Substack, 31 October 2022.

[24] Dylan Bugden, ‘Does Climate Protest Work? Partisanship, Protest, and Sentiment Pools’, Socius, 6, 2020

<https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120925949>

[25] If that sentence makes you feel uncomfortable to read (and, for what it’s worth, it made me feel uncomfortable to write) that speaks to the fact that Nope is just as provocative and incendiary in its own way as Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (2000). Peele is drawing connections between the exploitation of non-human animals and the exploitation of Black bodies and labour in this film. If hustle culture just leads to more Black CEOs and entrepreneurs, he seems to argue, those individuals will just find new others to exploit, which/ who may well have just as much cognisance as Black and white human beings. This argument inevitably makes me think of the outrage that always greets PETA when they compare atrocities against animals to atrocities against humans, such as comparing factory farming to the Holocaust. The argument that they are not the same thing rests on an anthropocentric principle that the human experience of the world is special in a way that means we should be protected from suffering and granted certain rights. The fact that most vegans would be vastly more upset by accidentally running over and killing a human child than they would a snail suggests that this anthropocentric bias generally overwhelms ideological conviction… however, the strength of this bias does not touch the logic of PETA’s argument, even while it makes it feel objectionable. Finally, of course, the unknowable other is not an unknowable other to him/her/itself unless indoctrinated and subjegated into being so.

[26] Salvage Editorial Collective, ‘The Tragedy of the Worker: Towards the Proletarocene’, Salvage, 31 January 2020.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Sam Kriss and Ellie Mae O’Hagan, ‘Tropical Depressions’, The Baffler, no. 36, September 2017.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ryan Meehan, ‘When Propaganda Fails: Adam McKay's "Don't Look Up"’, Mubi Notebook, 3 January 2022.

[31] Eric Roston, ‘climate change is weird’, @eroston, Twitter, 21 January 2020

<https://twitter.com/eroston/status/1219643845329199105>

[32] Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World, 2013.

[33] For instance, while we might argue that the 20,000 individuals who died from the heat waves across Europe in 2022 died “due to climate change”, it is highly unlikely that any of those individuals experienced their deaths as such. When I was hit by a car a few years back I didn’t think “I’m about to die, I’ve been killed by industrial modernity”, I thought, “I’m about to due, I’ve been hit by a car”.

[34] James Bradley, ‘The Library at the End of the World’, Sydney Review of Books, 13 October 2020.

[35] Not a perfectly idyllic exchange in terms of power relations, but it was, at least, a participatory and enjoyable exchange, to memory. Perfect should not be the enemy of good.